This post was the basis for a joint event with the grokking engineering community in Saigon.

The event was centered around DevOps, for our talk Docker Saigon needed to interest an engineering audience with how things tick on the inside of Docker. Audience experience with Docker and Linux operating systems was expected.

Anyone interested to learn more about Docker, Full free hands-on-labs training events are scheduled for 23⁄24 March. For more details go to meetup.com/Docker-Saigon

Outline

-

What is a Linux container, some history about Linux containers. How do they relate to Package Managers, Configuration Management, …?

-

Namespaces, cgroups, Images, Layers & copy-on-write

Overview of Container Runtimes

Past, Current and Future

-

With a focus on Events & Hooks

-

Evolution towards a common standard?

Overview of Linux containers

The target of this section is to give a very short overview of containers from a Linux system perspective, it is not meant as an introduction to users unfamiliar with Docker nor people unfamiliar with Linux systems.

Developers in Saigon looking to find out more on how they can get started with Docker, are referred to the excellent Installation Guide (OSX/Windows) and User Guides available on the Docker website.

Anyone wondering if/why Docker matters, is invited to contact the Docker Saigon user group (preferably through our Slack auto-invite app) for discussion.

What is a container?

In 4 bullet points:

- Containers share the host kernel

- Containers use the kernel ability to group processes for resource control

- Containers ensure isolation through namespaces

- Containers feel like lightweight VMs (lower footprint, faster), but are not Virtual Machines!

Components of a container ecosystem include:

- Runtime

- Image distribution

- Tooling

Now… if you look in the Linux kernel, there is no such thing as a container… so what gives?

History of Container Technology

- Chroot circa 1982

- FreeBSD Jails circa 2000

- Solaris Zones circa 2004

- Meiosys - MetaClusters with Checkpoint/Restore 2004-05

- Linux OpenVZ circa 2005 (not in mainstream Linux)

- AIX WPARs circa 2007

- LXC circa 2008

- Systemd-nspawn circa 2010-2013

- Docker circa 2013

- built on LXC

- moved to libcontainer (March 2014)

- appC (CoreOS) announced (December 2014)

- Open Containers standard for convergence with Docker Announced (June 2015)

- moved to runC (OCF compliant) (July 2015)

- … many more container formats coming?

How do containers compare to Package Managers?

Why are containers different from package management?

Packaging into an image is similar to an RPM, but apart from the Linux distributions - software is rarely packaged correctly.

The big innovation of Docker is that it is a slightly easier to use Package Manager. Package managers failed us due to shared libraries version differences causing dependency issues, packaging shared libraries in an image goes around that.

What is missing?

Package managers provide an easy way to find out what is inside the packages. If you are wondering how to handle this with Container Images…

See the Dockercon EU talks where a system of meta data tags was suggested for image inspection. See Shipping Manifests, Bill of Lading and Docker Metadata and Containers - Video

How do containers compare to Configuration Management?

Configuration Management utilities provide the ability to store Infrastructure as code. Popular CM tools include:

Several of the above tools are often still procedurally provisioning the environment as opposed to distributing a package which is self-contained and runs in exactly the same way on the same architectures in every environment (environments may differ in Linux distribution [Ubuntu/redhat/..], scale [local laptop / server cluster/ …], …).

However, it is still advisable to leverage such a provisioning tool to bootstrap the Docker infrastructure, letting the Container Runtime layer take care of the application layer once it is ready.

In Summary, I believe the following key points drive the adoption of Docker containers:

Docker provides a self-contained image that is exactly that same image running on your laptop vs in the cloud while i.e. Puppet/Chef are procedural scripts that need to rerun to converge your cluster machines. This enables approaches also know as Immutable Infrastructure or Phoenix Deploys.

Docker is really fast, to stand up a container takes very few seconds! There is very little overhead (cpu, memory, io, image footprint, ..) enabling high density (such as running a full stack of containers on your laptop, if you use Puppet/Chef, you’d need to create several VM’s with a much heavier footprint).

The community adopted Docker quickly due to the ease of how to build an image, the Dockefile DSL is very simple and very powerful (you can use pure bash to build the image or you can use load python scripts or anything similar you are familiar with for machine configuration.

Why Docker?

Docker is currently the only ecosystem providing the full package:

- Image management

- Resource Isolation

- File System Isolation

- Network Isolation

- Change Management

- Sharing

- Process Management

- Service Discovery (DNS since 1.10)

How?

The target of this section is to have a very detailed look into each component in the Linux stack which make Linux Containers possible.

A higher level overview is available (and was used as a reference) in the Official Docker documentation)

UPDATE: See Also jfrazelle’s talk @ container summit February 2016

Kernel Namespaces

Allow you to create isolation of:

- Process trees (PID Namespace)

- Mounts (MNT namespace)

wc -l /proc/mounts - Network (Net namespace)

ip addr - Users / UIDs (User Namespace)

- Hostnames (UTS Namespace)

hostname Inter Process Communication (IPC Namespace)

ipcsNotable example using IPC = PostgreSQL

Cgroups

Kernel control groups (cgroups) allow you to do accounting on resources used by processes, a little bit of access control on device nodes and other things such as freezing groups of processes.

Ref DockerCon EU: jpetazzoni: What are containers made from, we attempt to provide here a summarized overview of this excellent presentation.

cgroups consist of one hierarchy (tree) per resource (cpu, memory, …) . for example:

cpu memory

├── batch ├── 109

│ ├── hadoop ├── 88 <

│ │ ├── 88 < ├── 25

│ │ └── 109 ├── 26

└── realtime └── databases

├── nginx ├── 1008

│ ├── 25 └── 524

│ └── 26

├── postgres

│ ├── 524

└── redis

└── 1008

We can create sub groups for each hierarchy, in the example above custom batch and realtime sub groups for the cpu resource were created. Each process will be in 1 node for each resource (pid 88 is in a node for the memory resource as well as the cpu resource, …)

Note: cgroups are system wide The feature is enabled / disabled at boot time and can not be controlled on a per process level

A closer look at each resource tree:

Memory cgroup:

The Memory resource provides 3 types of functionality: Accounting, Limits & Notifications

Accounting

granularity = memory page size (4kb depending on the architecture)

2 type of memory pages:

- file pages: loaded from disk (important because we know the data is still on disk and can be removed from memory, no need to swap when memory needs to be reclaimed)

- anonymous pages: memory that does not correspond to anything on disk, for this type we have to swap out if we want to reclaim this memory

Some pages can be shared, for example: multiple processes reading from the same files.

Create 2 pools for all pages:

- Active

- Inactive pages - keep often accessed pages into active set.

Each page is accounted to a group, shared pages are only accounted to 1 group and re-allocated to another group if that group goes away.

Limits

Each group optionally has 2 type of limits:

Hard limits: If the group goes above its hard limit, the group gets killed with an

out of memoryerror. (which is why it is a good practice to put a single process in a container)Soft limits: not enforced… except when the system starts to run out of memory. The more a process goes over its soft limit, the higher the chance pages get reclaimed for its group

There are 3 kinds of memories on which limits can be applied:

- physical memory

- kernel memory: to avoid processes abusing the kernel to allocate memory

- total memory

Note

oom-notifier

Provides a mechanism to give control to a user program to handle a group going over its limits by freezing the processes in the group and notifying user space. At this point the program handling the notification could kill the container, raise the limits or migrate the container.

Overhead:

Each time the kernel gives or takes a page to or from a process, counters are updated.

HugeTBL cgroup

Accounting for usage of huge pages by process group, ignoring for now..

CPU cgroup

- keeps track of user/system CPU time

- keeps track of usage per CPU

allows to set weights - not limits

Why no limits? On an idle host a container with low shares will still be able to use 100% of the CPU

CPUSet cgroup

Bind group to specific CPU

Useful for:

- Real Time applications

- NUMA systems with localized memory per CPU

BlkIO cgroup

Measure & Limit amount of blckIO by group, unless your processes do direct IO - setting limits may give surprising results.

net_cls and net_prio cgroup

Kernel will only tag the traffic and you are responsible for doing traffic control (tc)

Devices cgroup

Controls which group can read/write access devices. Can be used to prevent groups to read/write directly to disk drives, very important for containers

Typically with containers access to /dev/{tty,zero,random,null} are allowed and everything else is denied.

Why /dev/random? Because if you are generating encryption keys inside a container, you will quickly deplete the entropy unless you read it from the host..

Other interesting devices for containers:

/dev/net/tunif you want to do anything with vpn’s inside a container without polluting the host/dev/fusecustom filesystems in a container/dev/kvmto allow virtual machines to run inside a container/dev/dri&/dev/videofor GPU access in containers - (see NVIDIA/nvidia-docker).

Freezer cgroup

Freeze a whole group without sending SIGSTOP/SIGCONT to the group (without interfering in the process).

Useful for:

- cluster batch scheduling

- process migration - think CRIU

- debugging without affecting prtrace

How to manage cgroups with Systemd?

By setting the ControlGroupAttribute in the unit file:

.include /usr/lib/systemd/system/httpd.service

[Service]

ControlGroupAttribute=memory.swappiness 70

Or temporarily on a running process through:

systemctl set-property <group> CPUShares=512

To show all properties of an existing group:

systemctl show <group>

The above commands go behind the Docker daemon and may result in unexpected behaviour (i.e.: settings are reverted on container restarts)

Note: Docker 1.10 introduced the

docker updatecommand to change cgroup limits on the fly for certain attributes:Usage: docker update [OPTIONS] CONTAINER [CONTAINER...] Updates container resource limits --blkio-weight=0 Block IO (relative weight), between 10 and 1000 --cpu-shares=0 CPU shares (relative weight) --cpu-period=0 Limit the CPU CFS (Completely Fair Scheduler) period --cpu-quota=0 Limit the CPU CFS (Completely Fair Scheduler) quota --cpuset-cpus="" CPUs in which to allow execution (0-3, 0,1) --cpuset-mems="" Memory nodes (MEMs) in which to allow execution (0-3, 0,1) -m, --memory="" Memory limit --memory-reservation="" Memory soft limit --memory-swap="" Total memory (memory + swap), '-1' to disable swap --kernel-memory="" Kernel memory limit: container must be stopped

How does the kernel expose cgroups?

Groups are created through a pseudo file system, this is how systemctl applies your configuration changes:

mkdir /sys/fs/cgroup/memory/somegroup/subcgroup

To move a process, just echo the process id to the special tasks file in the path of the group:

echo $PID > /sys/fs/cgroup/.../tasks

IPTables (networking)

Isolation on the networking level is achieved through the creation of virtual switches in the linux kernel. Linux Bridge is a kernel module, first introduced in 2.2 kernel (circa 2000). And it is administered using the brctl command on Linux.

Linux bridges are heavily used for the setup of Linux virtualization & Software Defined Networking (SDN).

Network shaping and bandwidth control for Linux containers can be achieved through the use of existing technology such as tc, I will not attempt to cover this here.

Below is a quick demo on how Docker uses the Linux Bridge together with IPTables functionality to create isolated Container networks and expose container ports.

Container networking and port forwarding

We will be using an Alpine image with DNS tools such as dig and an exposed port:

docker build -t so0k/envtest - << EOF

FROM alpine:latest

MAINTAINER Vincent De Smet <vincent.drl@gmail.com>

RUN apk --update add bind-tools && rm -rf /var/cache/apk/*

EXPOSE 80

EOF

Create a test network

docker network create test

Run 2 containers to demonstrate the resulting Linux configuration:

docker run --net test -dit --name host1 -P so0k/envtest sh

docker run --net test -dit --name host2 -P so0k/envtest sh

docker ps

Overview of Linux bridges & IPtable rules:

brctl show

sudo iptables -nvL

Notice a port has been opened for each port exposed within the container image:

ss -an | grep LISTEN

With the default Docker configuration, a userland docker-proxy process is used:

ps -Af | grep proxy

be careful if you need to open a lot of ports…

docker run --net test -dit --name prangetest -p 76-85:76-85 so0k/envtest sh

Memory usage by these proxies:

ps -o pid,%cpu,%mem,sz,vsz,cmd -A --sort -%mem | grep proxy

You can disable the userland docker-proxies forcing Docker to usee the Linux kernel ‘hairpin’ forwarding mode (kernel >=3.6) with alternative

iptablerules. This will improve network performance and memory usage.Note if you do not use the docker-proxy - your other containers may not be able to connect without hairpin NAT setup…

Next, demonstrate some simple “Service Discovery” provided within Docker networks:

docker exec -it host1 ping host2

docker exec -it host2 netstat -an

docker exec -it host1 dig host3 +noall +answer +stats

Notice how the container has been re-configured by Docker for name resolution:

docker exec host2 cat /etc/resolv.conf

The dns process was injected into the container:

docker exec -it host2 netstat -an

more info on configuration of the embedded DNS. notice we can create container aliases and still create private links between containers where required.

Let’s demonstrate the isolation between separate container networks:

docker network create test2

docker run --net test2 -dit --name host3 -P so0k/envtest sh

docker run --net test2 -dit --name host4 -P so0k/envtest sh

Notice another Linux bridge was created for this network:

brctl show

sudo iptables -nvL

Confirm containers on the first network can not reach containers on the second network. (to really confirm this use the actual container IPs instead of hostnames)

docker exec -it host1 ping host4

Name Resolution was introduced with Docker 1.10 in Q1 2016. The Docker DNS server is not exposed to containers connected to the default Docker bridge for backwards compatibility. (Running containers without the --net parameter puts them on the default bridge):

docker run -dit --name def-host1 -P so0k/envtest sh

docker run -dit --name def-host2 -P so0k/envtest sh

No name resolution:

docker exec -it def-host1 cat /etc/resolv.conf

docker exec -it def-host1 hostname

docker exec -it def-host1 cat /etc/hosts

If these containers need to find each other, use links, just like it used to be before Docker 1.10

docker run -dit --name def-host3 --link def-host1 -P so0k/envtest sh

docker exec -it def-host3 cat /etc/hosts

If you want to expose additional ports to the public, here is an example for the containers connected to the Default bridge:

#forward packets from port 8001 on your host to port 8000 on the container

iptables -t nat -A DOCKER -p tcp --dport 8001 -j DNAT --to-destination ${CONTAINER_IP}:8000

Let’s revise the cgroup setup of all the containers created above as seen earlier:

sudo systemd-cgls

Security

- AppArmor & jfrazelle/bane

- Seccomp

- Capabilities

Currently no examples provided in this document… This is subject for further study.

Types of Containers

Given the above constructs, containers may be divided into 3 types as follows:

System Containers share rootfs, PID, network, IPC and UTS with host system but live inside a cgroup.

Application Containers live inside a cgroup and use namespaces (PID, network, IPC, chroot) for isolation from host system

Pods use namespaces for isolation from host system but create sub groups which share PID, network, IPC and UTS except the rootfs.

Note, current Pod implementations on top of Docker are sub optimal as a work around is needed to allow the sub groups to share namespaces (this is implemented through a sleep container which is essentially pid 1). Ideally something like systemd is used as the PID 1 to share the namespaces between the sub groups and chroot to separate the rootfs.

Reference Brandon Philips: Where We Are and Where We Are Going

Images & Layers

Images you create yourself or images created by others are stored in Docker Registries. These are public or private stores from which you upload or download images. Docker registries are the distribution component of Docker.

There are 3 choices for use of a Registry:

A Public Cloud-hosted registry. The Docker Hub is the default registry used by the docker client and source of Officially maintained Docker images, however alternatives exists such as Quay.io. Limited Private repositories may be created or purchased to enable a quick Docker adoption.

An On-premise registry, through the commercially offered Trusted Docker Registry, providing advanced configuration options, Logging, usage and system health metrics and much more…

A Self-hosted registry based on the official Open Source Docker Registry. This is a fully functional Registry which you can fully setup by yourself and is the basis on which the Docker Trusted Registry is built, but it does not provide advanced monitoring & access control as well as requires manual maintenance.

Each Docker image references a list of read-only layers that represent filesystem differences. Layers are stacked on top of each other to form a base for a container’s rootfs.

When the container starts, the Docker engine prepares the rootfs & uses chroot for the container filesystem isolation - similar to LXC. One big innovation of the Docker engine was the concept of leveraging Copy-On-Write file systems to significantly speed up the preparation of the rootfs.

Copy-On-Write

Before Docker, LXC would create a full copy of FileSystem when creating a container. This would be slow and take up a lot of space

When Docker creates a container, it adds a new, thin, writable layer on top of the underlying stack of image layers. This layer is often called the “container layer”.

All changes made to the running container - such as writing new files, modifying existing files, and deleting files - are written to this thin writable container layer.

by not copying the full rootfs, Docker reduces the amount of space consumed by containers and also reduces the time required to start a container. Below is a diagram showing multiple containers and its “container layer”, sharing

Union File Systems provide the following features for storage:

- Layering

- Copy-On-Write

- Caching

- Diffing

By introducing storage plugins in Docker, many options are available for the Copy-On-Write functionality, for example:

- OverlayFS (CoreOS)

- AUFS (Ubuntu)

- device mapper (RHEL)

- btrfs (next-gen RHEL)

- ZFS (next-gen Ubuntu releases)

A quick overview on when to choose which, is provided here, full details are on the excellent Docker Docs

- AUFS: PaaS-type work:

| Pro | Con |

|---|---|

| stable | high write activity |

| production ready | not in mainline kernel |

| good memory use | |

| smooth Docker experience |

Aufs3 default & recommended for Ubuntu currently

- devicemapper (direct-lvm): Paas-type work:

| Pro | Con |

|---|---|

| stable | ?? |

| production ready | |

| in mainline kernel | |

| smooth Docker experience |

The most stable configuration for production environments on RHEL, but requires daemon flags to overwrite the defauts.

- devicemapper (loop): Lab testing - this is default in Docker on RHEL, not recommended for production

| Pro | Con |

|---|---|

| stable | production |

| in mainline kernel | performance |

| smooth Docker experience |

Using a loopback mounted sparse file, additional codepaths and overhead does not suit I/O heavy workloads.

- OverlayFS: Lab testing

| Pro | Con |

|---|---|

| stable | container churn |

| in mainline kernel | |

| good memory use |

Hailed as the future, default on CoreOS, but less mature and thus potentially less stable…

but… ionodes problems if there is high rate of containers creation/removal so, not good for build pools..

- Btrfs: Build Pools

| Pro | Con |

|---|---|

| in mainline kernel | high write activity |

| container churn |

Overview of Container Runtimes

The target of this section is to play with other container runtimes (some of the past, some alternatives to Docker and some upcoming implementations)

LXC

Originally used by Docker as backend until libcontainer replaced it.

- Installing:

install bridge-utils libvirt lxc lxc-templates

- Available commands

lxc-attach lxc-config lxc-freeze lxc-start lxc-usernsexec

lxc-autostart lxc-console lxc-info lxc-stop lxc-wait

lxc-cgroup lxc-create lxc-ls lxc-top

lxc-checkconfig lxc-destroy lxc-monitor lxc-unfreeze

lxc-clone lxc-execute lxc-snapshot lxc-unshare

- Quick Guide to use an LXC based container of busybox

wget https://www.busybox.net/downloads/binaries/busybox-x86_64 -o busybox

chmod a+x busybox

PATH=$(pwd):$PATH lxc-create -t busybox -n mycontainer

lxc-start -d -n mycontainer

lxc-console -n mycontainer # (use CTRL-A Q to exit console mode)

lxc-stop -n mycontainer

lxc-destroy -n mycontainer

Interesting Read: Linux Containers without Docker using OverlayFS & Ansible.

the LXC project has been working on a more user-friendly Daemon similar to the Docker daemon called LXD since November 2014.

Systemd-nspawn

Originally created to debug the Systemd init system, future versions to be more integrated in the core of the OS (the most low-level and minimal approach to make containers native to the OS).

CoreOS Toolbox uses systemd-nspawn and CoreOS rkt builds on top of it.

- Installing:

Included with all recent Linux distribution releases..

- Commands available

systemd-analyze systemd-delta systemd-nspawn

systemd-ask-password systemd-detect-virt systemd-run

systemd-cat systemd-cgls systemd-loginctl

systemd-sysv-convert systemd-cgtop systemd-machine-id-setup

systemd-coredumpctl systemd-notify systemd-tty-ask-password-agent

systemd-inhibit systemd-stdio-bridge systemd-tmpfiles

systemdctl machinectl hostnamectl journalctl

- Quick Guide to a container deployment using systemd-nspawn

# Create an Image (fedora)

sudo yum -y --releasever=7 --nogpg --installroot=/mycontainers/centos7 \

--disablerepo='*' --enablerepo=fedora \

install systemd passwd yum fedora-release vim-minimal

# Change the root password in the image (through a shell in the rootfs)

sudo systemd-nspawn -D /mycontainers/centos7

passwd

exit

# Start the container as if booting into the container image

sudo systemd-nspawn -bD /mycontainers/centos7 -M mycontainer --bind /from/host:/in/container

# Get list of containers registered with machine

machinectl list

machinectl status mycontainer

# log into the container

machinectl login mycontainer

# or enter the running namespace

nsenter -m -u -i -n -p -t $PID

see also - Docker without Docker see also - Rubber Docker Workshop - Prep Slides

runC

Spun out via libcontainer from Docker Engine and made OCI compliant, currently core of Docker Engine

- Installing runC

apt-get update && apt-get install libseccomp2

curl -Lo /usr/local/bin/runc https://github.com/opencontainers/runc/releases/download/v0.0.8/runc-amd64

chmod +x /usr/local/bin/runc

- Building & Installing

On Digital Ocean Ubuntu 14.04 with Docker 1.10 image:

Build dependencies:

apt-add-repository -y ppa:evarlast/golang1.4

apt-get update

apt-get install make gcc g++ libc6-dev libseccomp-dev golang

Procedure

cd ~

git clone https://github.com/opencontainers/runc

cd runc

GOPATH="$(pwd)" PATH="$PATH:$GOPATH/bin" make

make install

cd ~

- Commands available

checkpoint pause

delete restore

events resume

exec spec

kill start

list help

Quick guide to container deployment using

runc& Docker shipping.Keep in mind that the Docker Engine does all of the below behind the scenes for us and appreciate the level of comfort it provides.

# Download an OCF compliant image (using docker for example)

docker pull busybox

# Create busybox/rootfs

mkdir -p busybox/rootfs

# Flatten the image layers & copy to rootfs

tmpcontainer=$(docker create busybox)

docker export $tmpcontainer | tar -C busybox/rootfs -xf -

docker rm $tmpcontainer

# Generate container spec file

cd busybox/

runc spec

# start the container

runc start test

# confirm we are now in busybox container

/bin/busybox

ps -a

Alternatively download image layers from a registry using tianon’s script download-forzen-image-v2.sh

Or with debootstrap …

cd ~

apt-get install debootstrap

mkdir -p debian_wheezy/rootfs

debootstrap --arch=amd64 wheezy debian_wheezy/rootfs

cd debian_wheezy

runc spec

runc start debian

You can use post-start hooks (in config.json) to call additional binaries/scripts to do things such as set up the virtual bridge and veth pair and iptable rules for your container.

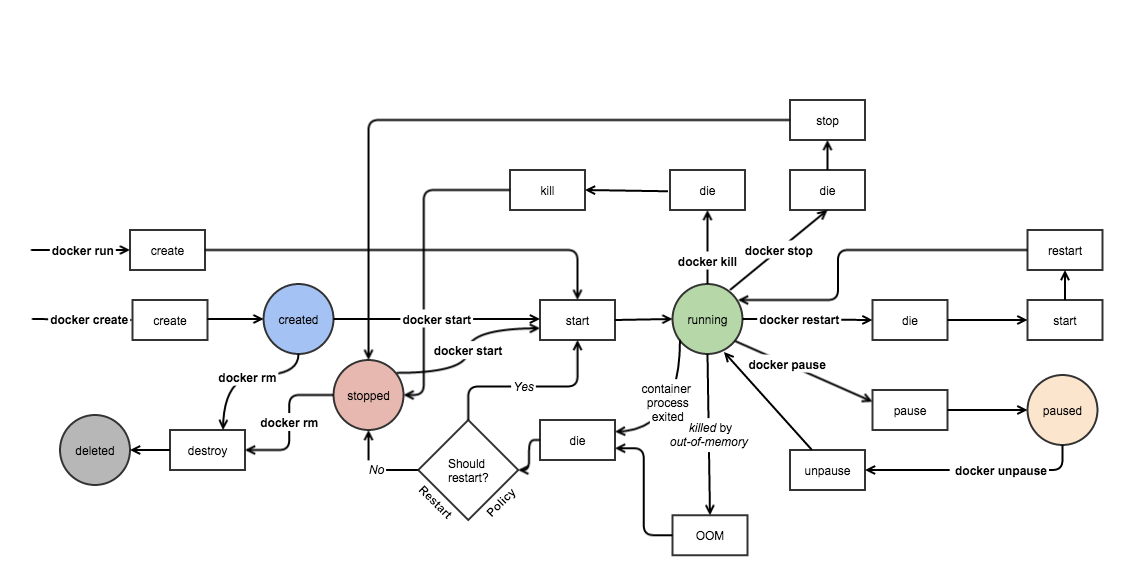

Docker API

The target of this section is to give an overview of how we might hook in to the various Docker components to leverage some of its notification systems. This is purely to quench the thirst of engineers looking to understand platforms built on top of Docker.

Many existing platforms already provide orchestration layers and it is advisable to research existing solutions before implementing your own using these events.

Docker Engine

Use Cases:

jwilder/docker-gen - simple implementation

docker-gen is a small utility that uses these APIs and exposes container meta-data to templates. Templates are rendered and an optional notification command can be run to restart the service.

Using docker-gen, we can generate Nginx config files automatically and reload nginx when they change. The same approach can also be used for docker log management.

Uses: fsouza/go-dockerclient

Code: How this registers Docker client & Passes events to listeners (Golang)

ehazlett/interlock - complicated implementation with extensions

Dynamic, event-driven extension system using Swarm. Extensions include HAProxy and Nginx for dynamic load balancing.

Uses: samalba/dockerclient

Monitoring with

docker statsand the API behind it? cAdvisor? more about monitoring: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sxE1vDtkYps&feature=youtu.be

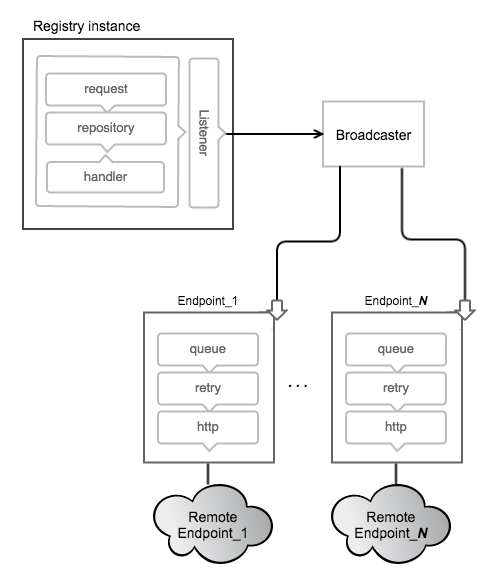

Docker Registry

Notifications through webhooks:

Use Case: conduit

Conduit exposes an endpoint that receives webhooks (i.e. from Docker Hub). Upon receiving the hook, Conduit will pull the new image, deploy a new container from the updated image and then remove the original container.

Docker Compose

Via stdout

See: Docker Compose events docs & PR

Sample gist (from PR):

#!/bin/bash

set -e

function handle_event() {

local entry="$1"

local action=$(echo $entry | jq -r '.action')

local service=$(echo $entry | jq -r '.service')

local hook="./hooks/$service/$action"

if [ -x "$hook" ]; then

"$hook" "$entry"

fi

}

docker-compose events --json | (

while read line; do

handle_event "$line"

done

)

Container Format explosion

As Docker made containers easy, an ecosystem emerged with an incredible amount of contributions towards the Docker standard.

However, different opinions exist concerning the exact requirements & responsibilities of each layer within a Container infrastructure with many big players looking to take a piece of the pie - divergence was to be expected.

The target of this section is to have a look at future and upcoming infrastructures. Out of these, Docker is currently (end 2015) the most mature and the easiest for beginning users to get started with.

Containerd (Alpha) - By Docker

See containerd.tools - Spinning out the Docker Daemon into a more advanced and OCI compliant Daemon to control runC.

Uses GRPC

A high performance, open source, general RPC framework that puts mobile and HTTP/2 first.

Containerd is the plumbing component that will manage containers in a future version of Docker Engine.

curl -Lo /usr/local/bin/containerd https://github.com/docker/containerd/releases/download/0.0.5/containerd

curl -Lo /usr/local/bin/ctr https://github.com/docker/containerd/releases/download/0.0.5/ctr

curl -Lo /usr/local/bin/containerd-shim https://github.com/docker/containerd/releases/download/0.0.5/containerd-shim

chmod +x /usr/local/bin/{containerd,ctr,containerd-shim}

nohup containerd >/dev/null 2>&1 &

Create redis image using Docker to pull from hub

mkdir -p redis/rootfs

docker pull redis

tmpredis=$(docker create redis)

docker export $tmpredis | tar -C redis/rootfs -xf -

docker rm $tmpredis

Prepare the OCI bundle:

generate config.json

runc spec

edit config.json:

- terminal: false

- populate uid & guid

- set

args: “redis-server”, “–bind”, “0.0.0.0” - set correct

cwd

edit runtime.json:

- remove

networknamespace for now to allow easy connections from localhost for testing…

see config.json & runtime.json from containerd repository

Or generate bundles from Docker container definittions with jfrazelle/riddler

OCI (OpenContainers Initiative)

OCI currently only covers the Runtime

Doesn’t cover how an image is defined, may cover Identity confirmation

Docker provided tech draft and implementation of OCI in runC (moving libcontainer to runC in the process).

- OCI? (simple tarballs of the layers+metadata being pushed)

The individuals behind the appc effort are joining the technical leadership of the OCI, and our intention is to work towards both a common format that is compatible with existing container formats as well as to work on a future spec that combines the best elements of all the existing container efforts.

See also CoreOS announcement & Docker announcement

Creating and maintaining formal specifications (“OCI Specifications”) for container image formats and runtime, which will allow a compliant container to be portable across all major, compliant operating systems and platforms without artificial technical barriers.

The idea behind OCI was to take the widely deployed runtime and image format implementation from docker and build an open standard in the spirit of appc.

AppC - By CoreOS

Ref (June 2015) Ref (Nov 2015)

- Image format (ACI) and Identity, initially based on Docker image format

- Container Signing

- Discovery mechanism allowing to easily store images and find where the images are (no default registry, no special registry)

- Runtime environment: defined behavior on running the images.

- Tooling: No fancy tooling required. For example, building is easy with command line tools

tar,gzipandgpgto sign them

Image Format

ACI (ref AMI) needs to contain all files and metadata needed to execute a given app.

Notable difference with Docker: ACIs need to specify the mount points…

Docker doesn’t require you to specify the volumes, it gives flexibility but you can’t read the image manifest and know all the required mountpoints. AppC can force volumes to be defined at run time and fail if they have been omitted.

rootfs: Same as in Docker image format. Could be an existing system, tarred up. Could be generated with

docker build. Could be build with native system tools Debian/Redhat tools to build full systems in a chroot.image manifest: all defined fields defined on the AppC repo. Key points are the concept of labels could be used to define the kernel requirements (Containers share the kernel) and explicit requirement on mountpoint definitions.

Images should be content addressable and share layers.

Discovery Mechanism

Translates an ACI name into a download-able image. All ACIs must have a detached signature and do a verification process.

Could be by convention using a template on the runtime.

Could be by probing a metadata endpoint to retrieve the discovery mechanism (if you want to use a different protocol, for example bittorrent to distribute your images)

Runtime Environment

AppC defines how ACIs are executed on a host. Fundamental concept is to allow multiple images to be running inside a container and define recovery policy for each image instance within the container.

Defines:

- FileSystem layout: uses the concept of Pod = ability to compose a collection of containers into a single execution unit.

- Volumes: There is a specific requirement to specify all mountPoints and it is the executer task to do that

- Networking (CNI): network plugins

- Resource Isolators: all cgroups should be defined when executing a container

- Logging: Runtime is responsible for having logs for all the Pods and the containers running in them

Tooling

Providing actool which allows you to actool build, actool cat-manifest, actool validate …

You can build with actool or the commandline tool listed above

Runtime may be able to convert Docker images on the fly, or you could use tools such as docker2aci to convert Docker images, deb2aci to convert packages … for you.

Image content verification, initial naive implementation is to use detached gpg signatures (basically you define what publicly signed hash you expect when downloading things over the internet), which is not ideal.

Upcoming standard for image verification is The Update Framework (TUF), which is adopted by Docker through Notary. TUF is similar to yum index / apt repo. Essentially a JSON file providing metadata of all images in a registry together with cryptographic metadata for verification once downloaded.

Existing Implementations of AppC

rkt

works in 3 stages:

- stage0: get the image, unpack, verify, ..

- stage1: runs the image (with nspawn) - currently launch systemd init system, processes run directly in process tree under assigned cgroup (not via a daemon).

- stage2: applying the isolators